Unfinished Obelisk

The Aswan Obelisk — the eighth wonder of the world, without exaggeration. It invalidates all versions of official history. Even the harshest skeptic, after becoming acquainted with the facts in this article (while in their right mind), will consider alternative versions of the origin of this megalith.

This is the first article of the project, and it is no coincidence that I chose the Aswan Unfinished Obelisk. I have personally studied it and now I want to share with you the results of my research. Let’s begin with its technical characteristics and with the refutation of the official version of history, which at first glance may sound quite convincing, but upon closer examination does not withstand criticism on any of its main points. For this refutation, I rely only on facts — both those I personally discovered and those well-known and easily verifiable by anyone.

The official version of history

According to the official version, the Aswan Obelisk was quarried out of the rock with dolerite cobblestones and hammers. Dolerite is a medium-grained analogue of basalt (feldspar + pyroxene). It is darker, denser, and harder than granite. In the Aswan quarries, dark veins, spots, and streaks are often visible running through the pink granite. We will talk about them separately below. To support the official version, right at the site there is a granite surface where tourists are invited to strike with a dolerite cobblestone. This way, anyone can see for themselves that pink granite is supposedly easy to work with a hand tool. Further, according to the official version, the quarried obelisks were loaded onto cargo ships and transported along the Nile to their destinations. All work was, of course, done by hand: large numbers of people, a complete absence of machine processing or metal tools, transportation on the ships of that era, and erection with ropes and animals.

Technical characteristics

Now that you are familiar with the official version, allow me to present the facts that refute its claims point by point. But first, for better understanding, let’s look at the technical characteristics of the unfinished Aswan Obelisk:

- Total length of the workpiece: 41.75 m

- Width at the “heel” (base of the shaft): 4.20 m

- Width at the base of the pyramidion: 2.50 m

- Height of the pyramidion (the upper “cap”): 4.50 m

- Estimated weight: ≈ 1168 English tons (≈ 1187 metric tons)

- Dating: New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, Hatshepsut (1473–1458 BC)

In other words, about 42 meters in length — roughly equal to a 14-story building — and weighing around 1,200 tons, which is approximately the same as 20 Abrams tanks or 6–7 modern locomotives. Already here, even healthy skeptics begin to doubt the official version, but the main part is still ahead.

I am personally convinced that this block was created using tools unknown to official history. And these tools left their characteristic traces all over the quarry. But let’s go step by step.

Refutation of the official version

The first issue is that very same stone block tourists are invited to “hit” with a dolerite ball. In reality, this is deception. Not a mistake, not a misunderstanding — but deliberate deception. The fact is, that piece is a loose, weathered chunk of granite that has cracked and completely lost its hardness. It can even be crumbled with your fingers. And yes, striking it with a dolerite stone (or any other) will indeed easily break pieces off. But the Aswan Obelisk itself consists of a different type of granite with a completely different density. This granite is so strong that a dolerite cobblestone bounces off its surface, leaving only minor scratches. Thousands of visitors to the site, myself included, have verified this. The thing is, the local red-pink Aswan granite (biotite–amphibole monzogranite with predominance of potassium feldspar and quartz) has a hardness of 6 on the Mohs scale, while dolerite (diabase), found in inclusions/dykes, has a hardness of ~7 Mohs. This makes it slightly harder, but still not capable of working pink granite. In other words, you can scratch the obelisk with dolerite, but you cannot quarry it out of solid rock.

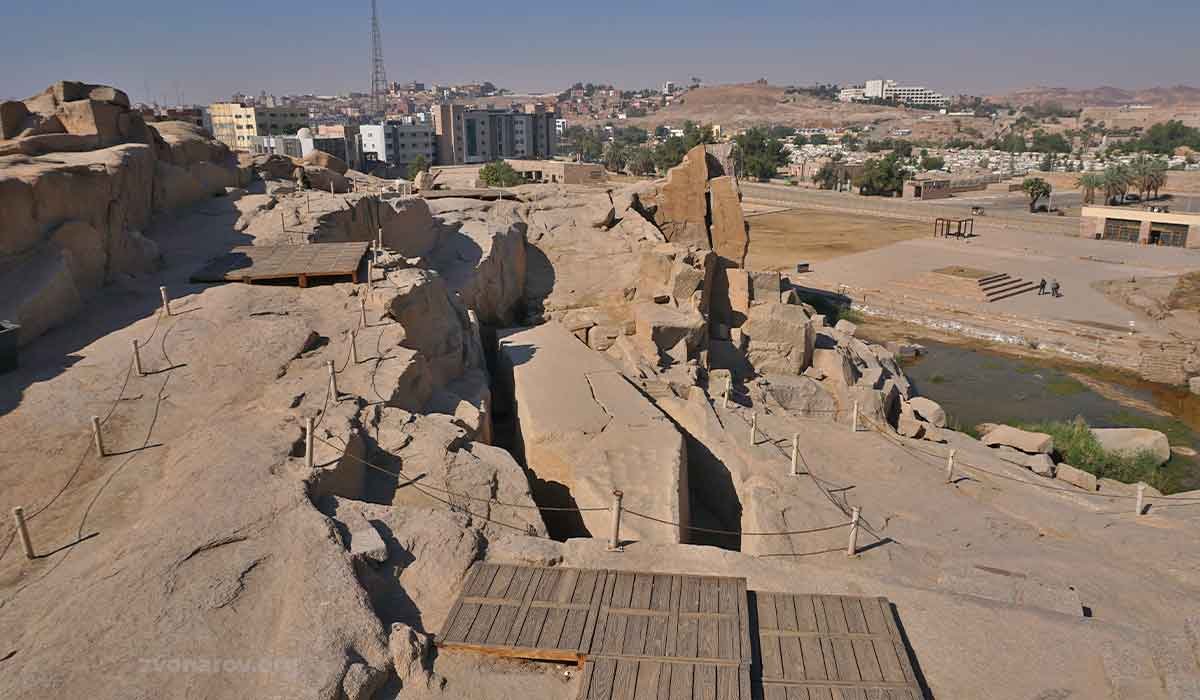

The second point, which completely invalidates the official version, is the characteristic inclusions on the obelisk itself.

Look at the photographs: dolerite inclusions in granite are clearly visible. They are CUT ALONG WITH THE GRANITE by some tool — and it certainly wasn’t a cobblestone. That is, the very same super-hard inclusions which, according to historians, supposedly served to pound out the obelisk, are themselves sliced together with the granite mass. Moreover, the cut surfaces are perfectly flat (as if polished), aligned in one plane along the entire length of the structure.

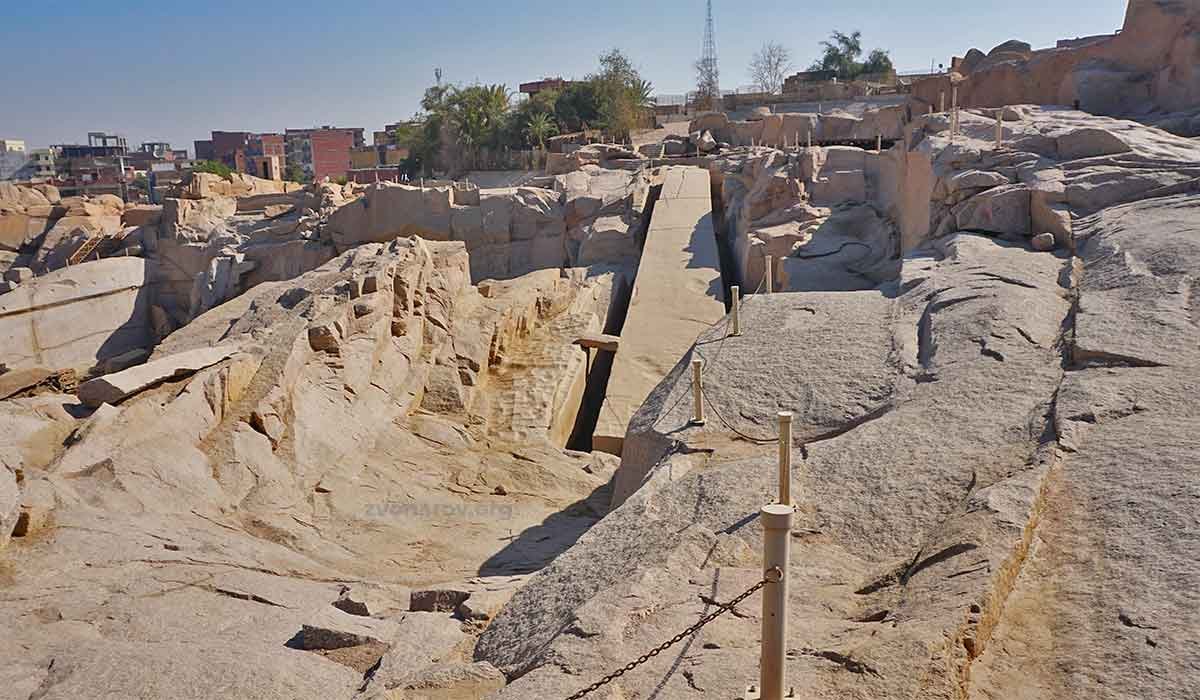

The next fact is the numerous marks on the granite block itself and around it. A simple look at their character shows that they are nothing like chips from striking with stone.

On the contrary, they are even, directed grooves, clearly left by a tool that removed layers of rock. Moreover, these grooves even indicate the width of this unknown tool.

Such marks are found not only on the obelisk itself but also in other areas of the Aswan quarries. These traces could easily be left, for example, in a huge piece of heated plasticine…

Photo: Ovedc, Wikimedia Commons, license CC BY-SA 4.0

The fourth fact, which does not fit at all with the official version of history, is transportation. Official historians cite the example of the Romans: they say the Romans transported obelisks by sea and erected them in Rome and in the Vatican, which is indeed true — I personally photographed those obelisks.

So, there were supposedly no problems, and it all sounds very convincing. But there are two big “buts.”

The first “but” — the obelisks the Romans transported weighed 4–6 times less than the Aswan Obelisk. For example, in 10 BC Augustus delivered from Heliopolis the Flaminio Obelisk weighing about 235 tons and the Montecitorio Obelisk weighing about 214 tons. During the reign of Caligula, the Vatican Obelisk (shown in the photo above) was transported, weighing around 330 tons. Let me remind you, the Aswan Obelisk weighs 1187 tons.

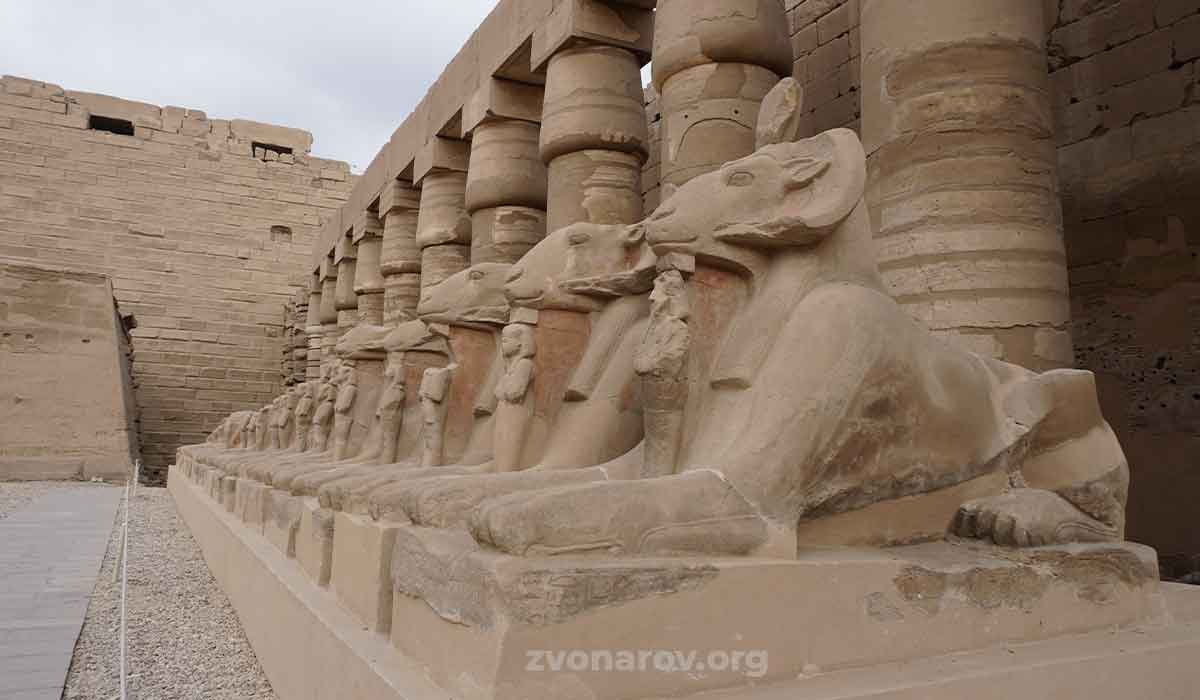

In the photo: the Temple of Hatshepsut in the City of the Dead (Luxor). Photo by Zvonarov.

The second “but” — historians somehow omit 1,500 years in these examples. According to the official version, the “commissioner” of the Aswan Obelisk was Hatshepsut — the New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, about 1473–1458 BC. That is, 1,500 years before cargo ships appeared that could carry loads 4–6 times lighter than required.

Hieroglyphic inscriptions on the walls of the Temple of Hatshepsut (Luxor, City of the Dead).

In Hatshepsut’s time, according to the official version, cargo ships were no more than 30 meters long (12 meters shorter than the Aswan Unfinished Obelisk) and had a maximum carrying capacity of no more than 20 tons — 60 times less than its mass. I hope the official version is clear enough now. Let’s now look at what else is interesting in this area.

Shafts and strange depressions

The shafts deserve special attention. They are everywhere in the quarry — both in the trenches running along the obelisk itself and in other places. These shafts, in principle, have absolutely no functional purpose.

They are simply holes cut into the granite mass. An enormous amount of work if done manually. If you try to hollow out such a shaft with a cobblestone, sand and dust would accumulate at the bottom, cushioning your blows, and one such shaft would take years to carve. Performing such colossal work without any practical purpose is at the very least strange.

Nevertheless, such shafts are found here everywhere and in large numbers. Their purpose remains unknown to official history, and this question is usually avoided, as if these shafts do not exist at all.

The picture becomes absurd: as if people spent centuries pounding granite with stones just for the sake of the process. Moreover, these shafts have straight edges, carefully worked bottoms, and are kept in plane quite neatly. Which means they were not only hollowed out but later also polished. Why?

Attempts to split granite

In the same quarries one can see many other traces — attempts to split stones, saw them, or make rough cuts. These traces show that it all ended in failure. The stones remained in place. In later times, with access to metal tools, Romans and other ancient peoples who came here tried to separate blocks for their needs. But even with metal tools they failed — which is not surprising, since the hardness of iron with carbon after quenching, as for example in the Roman period, could reach 5–6.5 on the Mohs scale, while pink granite often had the same or greater hardness.

The “Plasticine version”

There are also these kinds of traces. Let’s look at them again. I get the persistent impression that at some point a tool passed through soft stone, and then this mass solidified into hard rock. These very same lines are easy to leave in a soft material resembling plasticine. Hence the so-called “plasticine version.”

Here we see a V-shaped cut of unknown origin. What is strange about it? First of all, it is impossible to make such a cut with a cobblestone. To cut into granite in this way, a completely different tool is needed, along with a strong desire to leave exactly such a trace.

If we assume it was made later with a metal tool, two questions arise: first, why was it done at all, and second — how? Because to create such a form, the tool had to literally be driven into the stone, gradually scratching deeper, and then the resulting faces had to be polished.

Looking at the photo, I get the impression that the cut was made in a single motion. As if the hand slightly trembled, and the cutting tool left a slightly uneven, wavy line in the granite. But it is hard to imagine that such a trace came from a primitive hand tool. If it had been carved grain by grain, sand by sand, for months or years, it would make more sense to expect a straight line — since that would even be easier. But here, on the contrary, we see something like the trace of a casual hand movement, as if the tool passed over the stone easily and instantly.

In this video I am walking through the trench along the obelisk. Let’s look at the floor and walls. I do not get the impression that all this was done with a hand tool, especially not with a stone cobblestone. The surface is smooth. The characteristic traces on the floor rather point to excavation with some tool that immediately left behind even walls. I do not believe that these walls were leveled separately after the use of percussive techniques. And fine — the walls of the obelisk itself, that’s understandable: they had to be beautiful and straight. But why level the quarry walls? This is absolutely pointless and extremely labor-intensive.

The technology of extracting this block, as I have repeatedly said, was completely different. And although we do not know for certain what it was, at least independent researchers like myself are not afraid to say so. Unlike official historians and academics who supposedly “know everything.

”I state boldly: the deeper we study this object, the more questions arise. And to this day, no one knows the exact dates, methods of transportation, or ways of working this megalith.

Legacy of ancient Egyptian civilization

In conclusion, I want to say that the Aswan Unfinished Obelisk is only one small fragment of a vast megalithic picture stretching along the entire Nile and in other parts of modern Egypt. The scale of the blocks and structures is colossal. Scientists practically every month make new discoveries — finding blocks, cuts, shafts going hundreds of meters underground. The same applies to the already discovered “temples” and pyramids, the construction of which still puzzles modern scientists.

What impresses me is not even the fact of the existence of high technology in antiquity, but the volume of work that was carried out with its help. This knowledge, for some reason, was lost — as were the very bearers of these technologies. The civilization that existed then was highly advanced. It was from Egypt that the foundations of medicine, cosmetics, and culinary traditions emerged, which later became the basis of many world cuisines. Ancient knowledge still seems to reach us from there. I am convinced that this knowledge is the remnants of a once-existing civilization that left us all these mysteries.

The main one: what happened to these people? Why did such an advanced civilization, possessing unique technologies, not survive to our time? Why were many of their structures buried up to the top under a giant layer of sand, which we are still digging out today? Where did all this sand come from in such quantities? What else remains hidden beneath it?

Today, the Egyptian authorities do not allow access to these secrets not only for tourists but also for researchers. Underground passages are blocked by grates, armed guards stand at the entrances. Access to excavations of the main parts of sites is closed even to archaeologists.

I will continue to get to the truth step by step, conducting new research and making discoveries that bring us closer to solving the mysteries left by the ancient builders.

Thank you very much for reading this article. If you have the opportunity, please support the project — this will give me the means for new trips and new discoveries. This was Zvonarov. See you in the next publications.